Scientists have built microscopic, light-powered robots that can think, swim, and operate independently at the scale of living cells.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Michigan have developed the smallest fully programmable autonomous robots ever made. These tiny machines can swim through liquid, sense and respond to their surroundings on their own, operate continuously for months, and cost roughly one penny apiece.

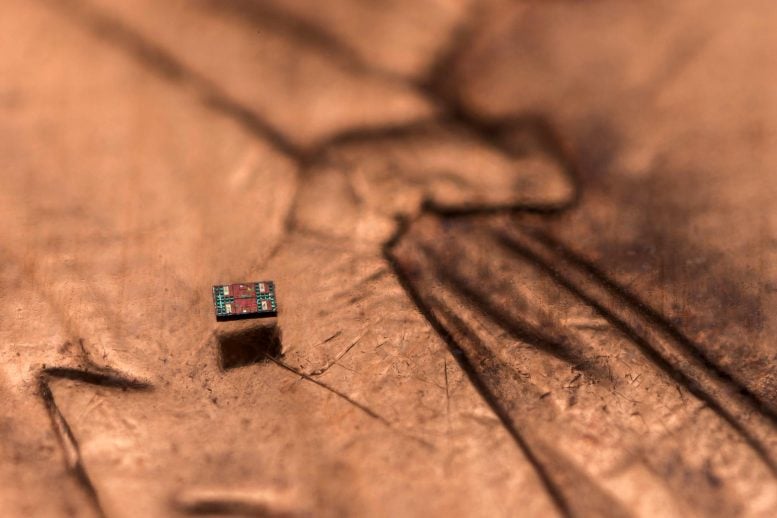

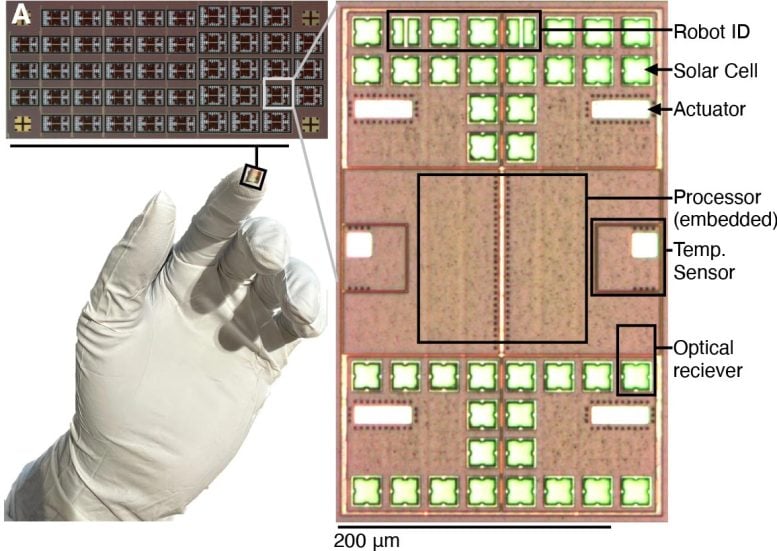

Each robot is nearly invisible without magnification. Measuring about 200 by 300 by 50 micrometers, they are smaller than a grain of salt. Because they function at the same scale as many microorganisms, the robots could eventually support new medical tools for monitoring individual cells and enable new manufacturing techniques for building extremely small devices.

The robots are powered by light and contain microscopic computers. They can be programmed to follow intricate movement patterns, detect temperature changes in their immediate environment, and alter their direction based on those readings.

Details of the work were published in Science Robotics and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Unlike earlier small-scale machines, these robots do not rely on wires, magnetic guidance, or external joystick-style control. That independence makes them the first programmable robots at this size that can truly operate on their own.

“We’ve made autonomous robots 10,000 times smaller,” says Marc Miskin, Assistant Professor in Electrical and Systems Engineering at Penn Engineering and the papers’ senior author. “That opens up an entirely new scale for programmable robots.”

Why building tiny robots has taken so long

Over the years, electronic components have steadily shrunk, but autonomous robots have not followed the same trend. According to Miskin, shrinking robots below one millimeter while keeping them independent has remained an unsolved challenge. “Building robots that operate independently at sizes below one millimeter is incredibly difficult,” he says. “The field has essentially been stuck on this problem for 40 years.”

The difficulty lies in how physics changes at small scales. In everyday life, motion is shaped by forces like gravity and inertia, which depend on an object’s volume. At the size of a cell, surface-related forces such as drag and viscosity dominate instead. “If you’re small enough, pushing on water is like pushing through tar,” Miskin explains.

Because of this, traditional robot designs fail when scaled down. Limbs and joints that work for larger machines become fragile and impractical. “Very tiny legs and arms are easy to break,” says Miskin. “They’re also very hard to build.”

To solve this problem, the research team created a new form of propulsion designed specifically for the physics of the microscopic world, rather than adapting methods used at larger scales.

[embedded content]

The robots, each smaller than a grain of salt, move by using an electrical field to manipulate the ions around them. They can sense temperatures, and could potentially advance medicine by monitoring the health of individual cells. Credit: Bella Ciervo, Penn Engineering

A new way to swim at microscopic scales

Fish and other large swimmers move by pushing water backward, generating forward motion through Newton’s Third Law. The microscopic robots take a very different approach.

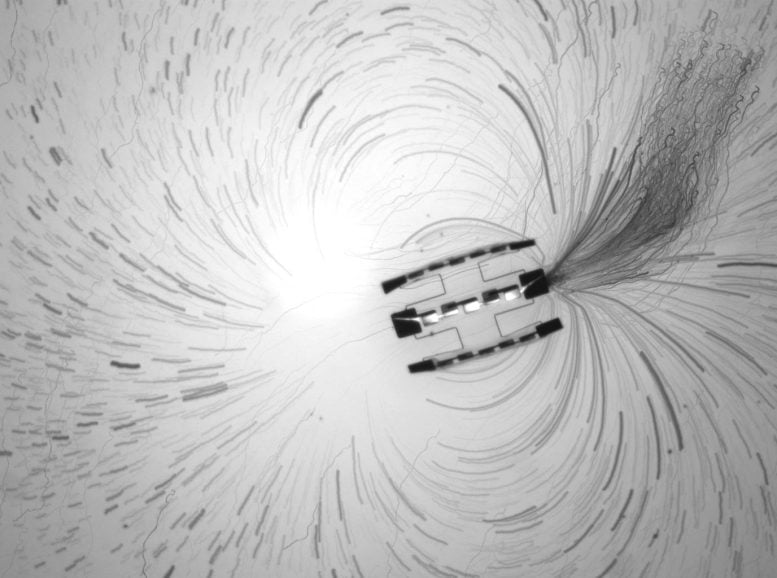

Instead of bending or flapping, the robots create an electrical field that gently moves charged particles in the surrounding liquid. As those ions shift, they pull nearby water molecules with them, setting the fluid in motion around the robot. “It’s as if the robot is in a moving river,” says Miskin, “but the robot is also causing the river to move.”

By tuning this electrical field, the robots can change direction, follow complex paths, and even move together in coordinated groups similar to a school of fish. They are capable of reaching speeds of up to one body length per second.

Because this propulsion method relies on electrodes with no moving parts, the robots are highly durable. According to Miskin, they can be transferred between samples multiple times using a micropipette without damage. Powered by light from an LED, the robots are able to keep swimming for months.

Packing intelligence into a microscopic robot

Autonomy requires more than movement. A robot must also process information, sense its surroundings, and power itself. All of those components must fit onto a chip measuring only a fraction of a millimeter. This challenge was addressed by David Blaauw’s team at the University of Michigan.

Blaauw’s lab holds the record for building the world’s smallest computer. When Blaauw and Miskin met five years ago at a Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) presentation, they quickly recognized how well their technologies fit together. “We saw that Penn Engineering’s propulsion system and our tiny electronic computers were just made for each other,” says Blaauw. Turning that idea into a working robot, however, required years of collaboration.

One major obstacle was power. “The key challenge for the electronics,” Blaauw says, “is that the solar panels are tiny and produce only 75 nanowatts of power. That is over 100,000 times less power than what a smart watch consumes.” To operate under such constraints, the Michigan team designed specialized circuits that function at extremely low voltages, reducing power consumption by more than 1000 times.

Space was another limitation. The solar panels occupy most of the robot’s surface, leaving little room for computing hardware. To address this, the researchers redesigned how instructions are stored and executed. “We had to totally rethink the computer program instructions,” Blaauw explains, “condensing what conventionally would require many instructions for propulsion control into a single, special instruction to shrink the program’s length to fit in the robot’s tiny memory space.”

Robots that sense and communicate

Together, these advances resulted in what the researchers describe as the first sub-millimeter robot capable of real decision-making. To their knowledge, no previous robot of this size has included a complete computer system with a processor, memory, and sensors. This achievement allows the robots to sense conditions and act independently.

Each robot is equipped with electronic sensors that can measure temperature with an accuracy of about one third of a degree Celsius. This enables them to move toward warmer areas or report temperature readings that can serve as indicators of cellular activity, providing a way to assess the health of individual cells.

Communicating that information required a creative solution. “To report out their temperature measurements, we designed a special computer instruction that encodes a value, such as the measured temperature, in the wiggles of a little dance the robot performs,” says Blaauw. “We then look at this dance through a microscope with a camera and decode from the wiggles what the robots are saying to us. It’s very similar to how honey bees communicate with each other.”

The robots are programmed using pulses of light, which also supply their power. Each robot has its own unique address, allowing researchers to assign different programs to different units. “This opens up a host of possibilities,” Blaauw adds, “with each robot potentially performing a different role in a larger, joint task.”

A foundation for future microscopic robots

The current robots represent a starting point rather than a finished product. Future versions could include more advanced programs, higher speeds, additional sensors, or the ability to function in harsher environments. The design serves as a flexible platform, combining a robust propulsion system with electronics that can be manufactured cheaply and adapted over time.

“This is really just the first chapter,” says Miskin. “We’ve shown that you can put a brain, a sensor and a motor into something almost too small to see, and have it survive and work for months. Once you have that foundation, you can layer on all kinds of intelligence and functionality. It opens the door to a whole new future for robotics at the microscale.”

References:

“Microscopic robots that sense, think, act, and compute” by Maya M. Lassiter, Jungho Lee, Kyle Skelil, Li Xu, Lucas Hanson, William H. Reinhardt, Dennis Sylvester, Mark Yim, David Blaauw and Marc Z. Miskin, 10 December 2025, Science Robotics.

DOI: 10.1126/scirobotics.adu8009

“Electrokinetic propulsion for electronically integrated microscopic robots” by Lucas C. Hanson, William H. Reinhardt, Scott Shrager, Tarunyaa Sivakumar and Marc Z. Miskin, 15 July 2025, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2500526122

The research was carried out at the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) School of Engineering and Applied Science, Penn School of Arts & Sciences, and the University of Michigan, Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. Funding was provided by the National Science Foundation (NSF 2221576), the University of Pennsylvania Office of the President, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR FA9550-21-1-0313), the Army Research Office (ARO YIP W911NF-17-S-0002), the Packard Foundation, the Sloan Foundation, and the NSF National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure Program (NNCI-2025608), which supports the Singh Center for Nanotechnology, along with Fujitsu Semiconductors.

Additional co-authors include Maya M. Lassiter, Kyle Skelil, Lucas C. Hanson, Scott Shrager, William H. Reinhardt, Tarunyaa Sivakumar, and Mark Yim of the University of Pennsylvania, and Dennis Sylvester, Li Xu, and Jungho Lee of the University of Michigan.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.